This post continues the journey of implementing a MongoDB repository, this time focusing on the search implementation.

Implementing the Product Repository (continued…)

I structured my API for search to allow me to pass in the property I want to search on and a search value for that property. The goal here wasn’t to be a rich searching engine but instead to give some common scenarios and see how they could be implemented. A few examples of search URL’s I wanted to support are…

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

// Find products whose Name field contains “sql”

GET /api/product/search?property=name&value=sql

// Find products whose Price field equals 19.99

GET /api/product/search?property=price&value=19.99

// Find products in the "clothing" category

GET /api/product/search?property=categories&value=clothing

I also wanted to be able to do searches on properties/fields that are unknown to the base Product model.

1

2

3

4

5

// Find products with a “Fabric” property equal to “cotton”

GET /api/product/search?property=Fabric&value=cotton

// Find products with a "Voltage" property containing "18"

GET /api/product/search?property=Voltage&value=18

Finally, I want all the searches to be case-insensitive, matching substrings (not just full string matches).

What I ended up with was a generic, yet powerful, search method. When I first started this, I thought I would have a search method using LINQ queries against my base Product model and another method for everything else. And that was what my first pass at this actually was. More on that later. However, after experimenting more with the API’s, I was able to get all my search requirements down to one short method that I’m mostly satisfied with.

When searching on properties that are in in my base Product model, I was able to be very precise about the search implementation. For example, since I know about the properties in my model, I can correct casing of the property name before issuing the query. Or, if the property is a complex type (array, nested document, etc.), then I can adjust the query for that particular type.

As I expanded my search capabilities beyond my model to any property that any product might have, things got a little thorny. For example, if I want to search on the “Voltage” property (a property not in my model), then the URL needs to specify the exact casing of that property (“Voltage” not “voltage”). And, who’s to say that some product in the collection may actually have a “voltage” property now, or in the future. In which case, a search on “Voltage” and a search on “voltage” would yield two different results. Not good! Another issue is searching properties unknown in my model that have complex structures. A lack of a model for these additional properties makes searching on them extremely challenging. In my implementation, I treat anything I don’t know about as a simple string search.

The point of all this is to support a point I made in an earlier post. Which is, just because you can store any random document into a collection, doesn’t mean you always should. Properties in your documents should be consistently named (and cased) throughout the collection. Try to think ahead about how you intend to use and query the documents in the collection and structure your model (schema) to support those needs. That was the basis for my Product model (although very small). It enables me to have some consistency throughout the collection. Without it, searching the collection would otherwise have been very challenging.

Now, on to the code…

The Search Implementation

In the constructor for my repository, I added this line of code to reflect over my base Product model, giving me a list of PropertyInfo objects that I can leverage in my search method. This is just the way I chose to do this. If you use the LINQ query support then this is not necessary.

1

2

// Get a list of properties I know about (from the model).

knownProperties = typeof(Product).GetProperties().ToList();

My search method starts off like this, taking advantage of the knownProperties list. All I’m doing here is properly casing the srchProperty when the property specified is one I know about.

1

2

3

4

5

6

// If this is a property/field I know about, then I can be more

// precise about how I construct the query.

var knownProperty = knownProperties.Find(p => p.Name.ToLower() == srchProperty.ToLower());

// Set the name of the property to exactly match casing.

srchProperty = (knownProperty != null) ? knownProperty.Name : srchProperty;

Next, I setup my default query. This query does a simple string search on the srchProperty to see if the value contains the srchValue. It also ignores casing inconsistencies.

1

2

3

4

5

6

// Query for searching a property's value.

// This is the default query unless otherwise specified.

IMongoQuery query = Query.Matches(

srchProperty,

new BsonRegularExpression(

new Regex(srchValue, RegexOptions.IgnoreCase)));

If the search is on a property that is in my model, then I can leverage what I know about the property to make the search more intelligent. My Product model contains 3 different types of properties (string, double, and List<string>). Since my default query (above) already handles string, I just need to handle the other two types in my model.

The first type I handle is the double, which is what my Product.Price is. Since the parameter is passed in from the URL as a string (again, that’s my default), I simply convert it to a double and overwrite query with a precise query for double.

Next is the List<string> type, which is what Product.Categories is. These 2 lines of code overwrite the query to search the list of categories for each product, matching any product whose category(s) contain the srchValue passed in. In other words, I can search for “book”, “Book”, or even “OOK” and I’ll get back the same list of products. Again, having a model you can reference makes implementing the query very easy and more powerful.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

if (knownProperty != null)

{

if (knownProperty.PropertyType == typeof(double))

{

double srchDouble;

if (double.TryParse(srchValue, out srchDouble))

query = Query.EQ(knownProperty.Name, srchDouble);

}

else if (knownProperty.PropertyType == typeof(List<string>))

{

var rx = new Regex(srchValue, RegexOptions.IgnoreCase);

query = Query.All(knownProperty.Name, new List<BsonValue>() { BsonValue.Create(rx) });

}

}

For searches on properties I don’t know about, I default to the string query (above). However, in this case, I need to tell MongoDB to also check if the property exists because now I’m searching on properties that not all documents in the collection will have.

1

2

3

4

5

// A query to check if the property exists in the collection.

var qPropExists = Query.Exists(srchProperty);

// Pull the two query conditions together into one query.

query = Query.And(qPropExists, query);

Finally, I issue the query and return the results.

1

2

return MongoHelper.ProductsCollection.FindAs<Product>(query).

Skip(pageIndex * pageSize).Take(pageSize).ToList<Product>();

Query Builder or LINQ

Why did I choose this approach over using LINQ for queries against my Product model? I wanted to support queries against my model and queries on properties that are not part of my model in as few lines of code as possible. By taking this approach, I was able to have just one line issue the query to MongoDB. The only difference is how the query is constructed.

There was also a “gotcha” I ran into using LINQ that I was able to easily resolve using the Query builder approach. Recall that I wanted my searches to be case-insensitive. At first I thought this would be very easy using LINQ. After all, this line of code compiles just fine!

1

2

productQuery = MongoHelper.ProductsCollection.AsQueryable<Product>().

Where(p => p.Categories.Contains(srchValue, StringComparer.CurrentCultureIgnoreCase));

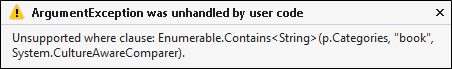

However, when I ran it, I got this runtime exception.

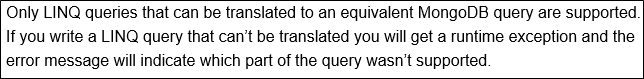

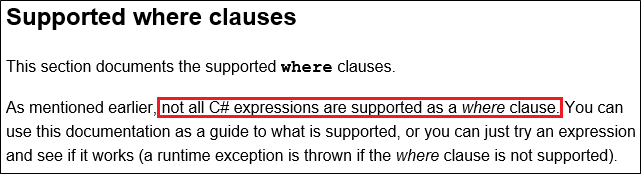

In fact, this condition (and potentially others) is documented here.

and here…

Bummer! This was the only condition like this I discovered. Otherwise, the LINQ support was fantastic.

Anyway, there were a couple of easy ways to resolve this. I chose to do so using the Query builder approach, incorporating a simple regular expression into my query (see above). Not only was I able to achieve a case-insensitive search on the Categories property, but I was also able to easily support substrings of the category being searched for – something my LINQ query wouldn’t have done even if it was supported.

Conclusion

Using Fiddler (or a browser since these are GET operations), it is easy to search the products catalog. My full implementation is available here for anyone interested in trying it out.

MongoDB supports very powerful queries across collections, regardless of the schema (or lack of) from one document to the next. This post showed how you can use the MongoDB C# drivers to query the database. More importantly, I hope it illustrates how having some degree of schema in your application model will help query the collection effectively.

Comments powered by Disqus.